We continue our summer series with the geology of Paris, and more specifically the geology of the Olympic Road Race. When the riders start to climb Butte Montmartre and Butte Belleville during the final kilometers of the Olympic Road Race, they won’t ask themselves why those hills are there. The only things going through their minds are gold, silver and bronze. But we do wonder, of course. What is the origin of all those hills at Montmartre and Belleville? Let’s dive into the geology of Paris.

Shaped by Seine and Marne

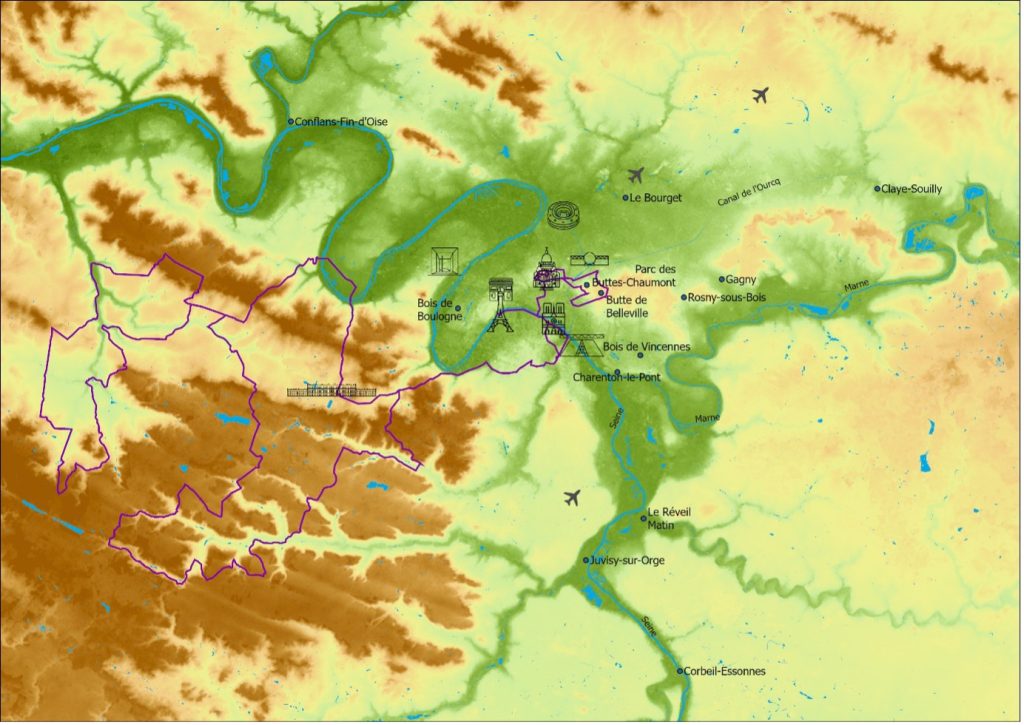

When you look on the elevation map of Paris and its surroundings, you immediately notice that the city centre of Paris is in the heart of a wide valley. This valley was shaped by the river Seine and its main tributaries like the river Marne.

The Seine meanders graciously from near the Eiffel Tower on both sides of Bois de Boulogne to the area near Stade de France in Saint-Denis. From there, the Seine meanders through a fairly narrow valley towards Rouen before flowing out into the sea at Le Havre. You see the same pattern of fairly narrow valleys carved by rivers on the east and south sides of the city centre. Read more about the Paris Basin here.

The elevation map shows clearly how the river Seine has carved itself relatively deep into the landscape south of Paris to form a narrow valley along place like Le Réveil Matin, Juvisy-sur-Orge and Corbeil-Essonnes. Fun fact: Le Réveil Martin is where the very first Tour de France started in 1903. The river Marne also carved a narrow valley at the east side of the city centre to form the Val-de-Marne (literrally valley of the Marne). It’s at Charenton-le-Pont that the Marne flows into the Seine.

Up the hill

When you look closer to the elevation map above you see that the Arc de Triomphe, Sacré-Coeur on Montmartre, as well as the park of Buttes-Chaumont on Butte Belleville are on top of local hills. These relatively elevated hills are surrounded by the valleys carved by the Seine in the south, the Marne in the east and finally a large low-lying plain in the north. This large low-lying plain extends from the Stade de France in the west to about Claye-Souilly in the east. At Claye-Souilly, this plain connects to the valley of the Marne via a narrow passage.

Two things are remarkable about this low-lying plain. First, this plain is relatively wide compared to the valleys of the Seine and its tributaries. Moreover, it is also notable that no major river flows in this plain. You only find some minor streams and narrow canals like the Canal de l’Ourcq there. You might therefore wonder how it is possible that in absence of a large river such a large plain is there.

Geologists were also looking for a good explanation for that. Only recently and after specific research they found a good answer to this question. The presence of gypsum, and the Seine and Marne rivers play a key role.

Geology of Paris shaped by gypsum

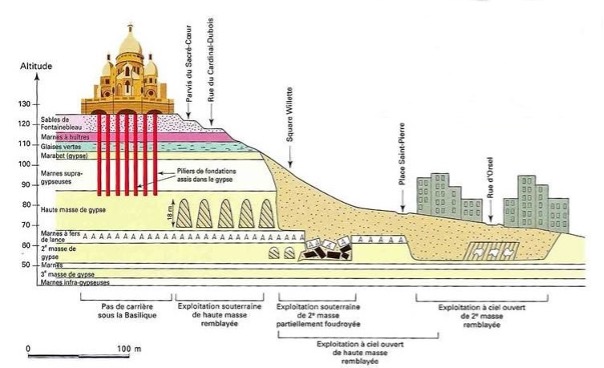

Thick layers of gypsum are present in the subsoil of the Montmartre and Belleville hills. Gypsum is a soft material frequently used as a building material. We know from archaeological research that the inhabitants of Paris during Roman times already extracted gypsum from the subsoil near these hills to use for building houses.

Because of the great need for building materials the mining of gypsum continued until the mid-19th century. Meanwhile, the growing city also began to experience the negative effects of gypsum mining. The many quarries hindered the city’s expansion because of problems with the stability of the subsoil. Local land subsidence due to the gypsum quarries is still common in the northern part of Paris today. For the construction of the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur at the top of Montmartre around 1875, it was necessary to fill numerous quarries in the subsoil with rubble and concrete in order to get a sufficiently solid foundation to support the enormous weight of the church.

The collapse

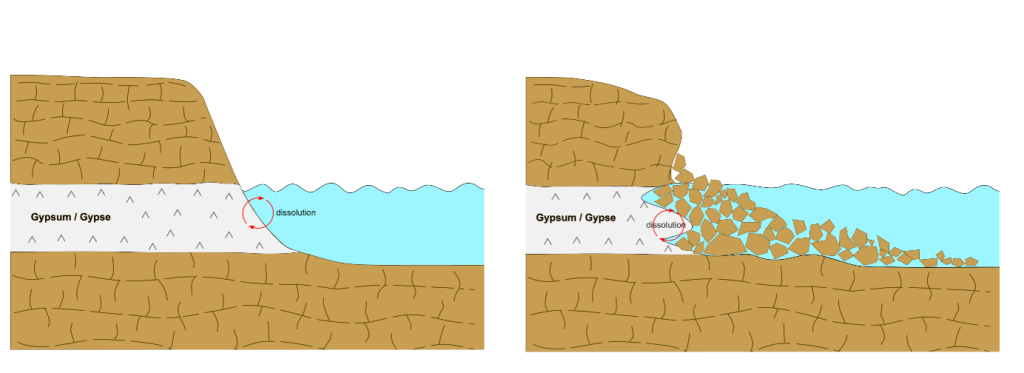

Gypsum is a soft mineral of ions of calcium and sulphate. It is formed at locations where an influx of mineral-rich water – such as seawater – evaporates faster than it can flow away. This is how you get the so-called evaporites. This happened around 35 million years ago where we now find Paris. Because gypsum is the result of seawater evaporation, it will also dissolve relatively easily when exposed to water that is less mineral-rich. Think of rainwater, river water or shallow groundwater. This happened at the time when the precursors of today’s Seine, Marne and other rivers arrived in Paris.

In areas where gypsum comes into contact with mineral-poor water, it gradually dissolves. As a result of the dissolution of gypsum, steadily growing cavities form in the subsoil. At some point, the remaining gypsum will no longer be able to support the weight of the rock above it. The hill will collapse.

Eating away

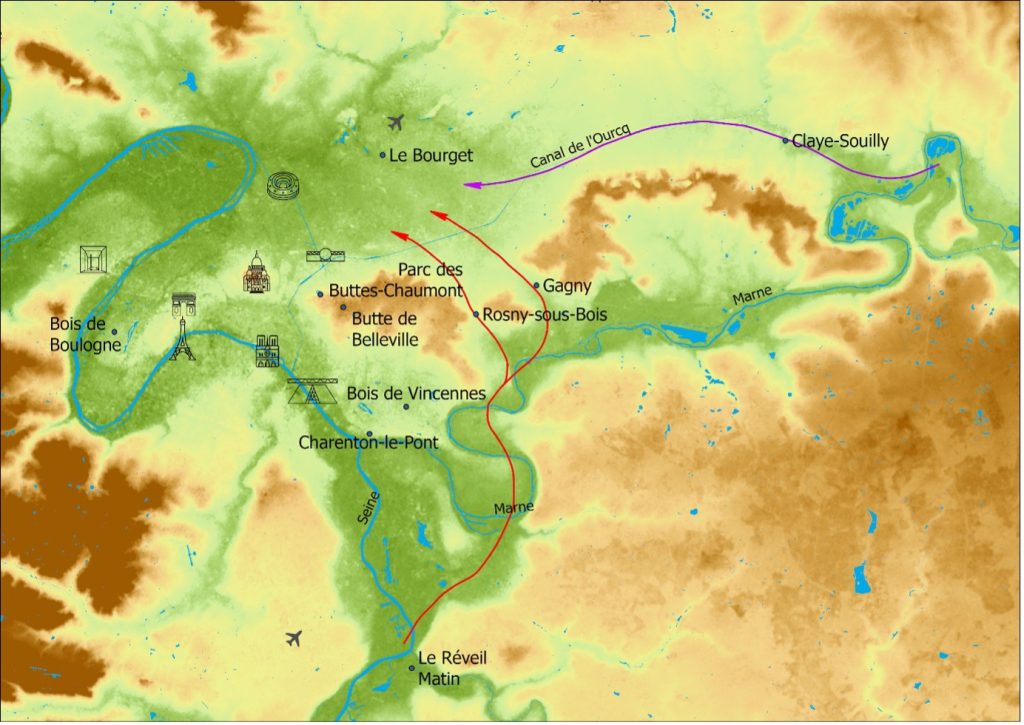

We already learned that contact between mineral-poor water – for example river water – and gypsum causes steady dissolution of gypsum situated in the subsoil. As a result, overlying geological layers become unstable and even collapse like you saw in the image above. That is exactly what happened near Rosny-sous-Bois, Gagny and Claye-Souilly where we find the plain now. The predecessors of the rivers Marne and Seine ate away the gypsum and opened new routes for the rivers to flow.

The Seine flows through Paris but an alternative route along the north side of Montmartre and Butte Belleville is important to explain the presence of our Olympic Road Race hills. The water on the northern route frequently came into contact with the gypsum layers there. The process repeated. They dissolved and this caused more and more rock to become unstable in those places. The rock collapsed and fell into the river. From then on, the river had the opportunity to further break down this debris via erosion and transport the remains to the sea. As time went on, an ever-larger low-lying plain gradually developed at the north side of Montmartre and Buttes-Chaumont.

Last hills standing

The water of the precursors of today’s Seine and Marne created two fully-fledged routes through the Paris region. Even at high water there was sufficient capacity and space available for the flowing water. As a result there was no need for the water to erode the remaining rock, like the rocks that form Montmartre and Butte Belleville, any further. In short there was enough room for the water to now leave the hills alone. The ones that remained are the residual hills or, in French, ‘buttes’.

The Butte Montmartre and Butte Belleville were the ones spared from erosion that flattened its brother and sisters around the city. Nevertheless there will be plenty of riders who had hoped the precursors of Seine and Marne also would have cleaned up these hills . It would have saved them a lot of energy on their way to the finish line. However, anyone who wants to be on top of Mount Olympus should at least to conquer these residual hills. Cycling is after all often a fight against geology, also in Paris.