Germany has everything to offer for fans of both geology and cycling. While sediments are currently accumulating in the German Wadden Sea, the oldest rocks in Germany formed more than two billion years ago. In-between these two extremes, there are rocks and sediments that tell us a story about ice ages, sea level change, mountain building, meteorite impacts, volcanism, sedimentation and erosion. Geologists and cyclists alike subdivide Germany in three main areas for this geology of the Deutschland Tour.

The lowlands of northern Germany are the perfect setting for flat sprint stages, such as the opening stage of the Deutschland Tour. This is the favourite terrane for riders like Mark Cavendish or Caleb Ewan. This part of Germany has been tectonically subsiding for more than hundred million years, forming a layer cake of sedimentary layers in the subsurface.

South of the lowlands, the landscape becomes hillier and the outcropping rocks become older. Here, a wide variety of rocks can sediments can be found. This part of Germany is a veritable patchwork of geological blocks, each with its own tectonic history. During the second, third and fourth stage of the Deutschland Tour, we will look a little more closely at the history of some of these blocks.

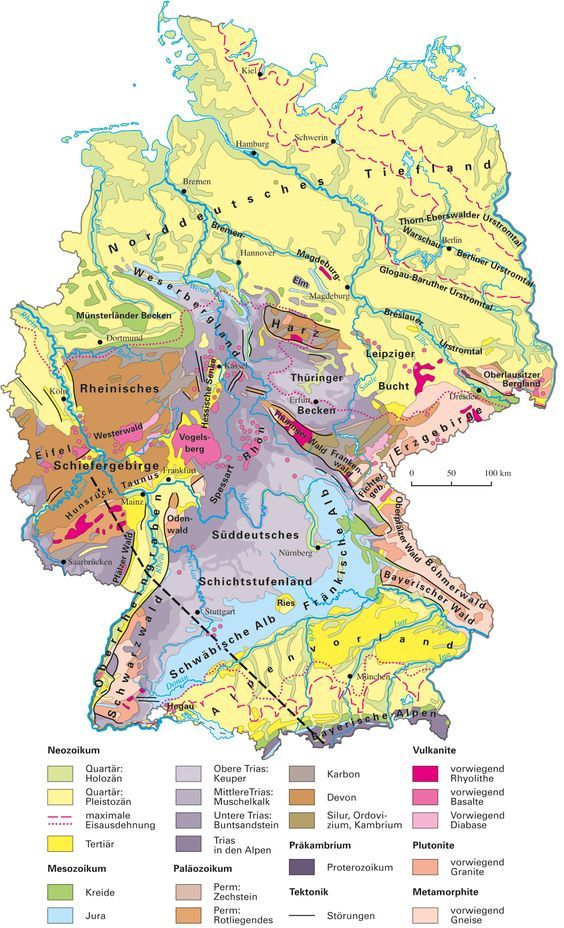

The main differences between rock types in this large area are determined by the amount of pressure and temperature the rocks have been subjected to. Metamorphic crystalline areas, like the Black Forest or the Bohemian Massif, were strongly affected when they were deeply buried during a mountain building phase, some 300 million years ago. They show up as reddish and grey-brown colours on the geologic map.

The so-called “slate belts” (e.g. Rhenish Massif, Harz, Thuringian Slate Mountains) were folded, but not deeply buried. They show up as orange-brown and greenish colours on the geologic map. In-between the slate belts and crystalline massifs. One finds unfolded sedimentary rocks of the Mesozoic Era (purple colours: the time of the dinosaurs!), the alpine foreland in yellow colours, and the Rhine graben. This hilly landscape offers opportunities for riders with explosive power. Think about for example Michael Woods and Tom Pidcock., This is exactly what we’ll see in the first, second, and third stages of the Deutschland Tour.

The third and last main geologic area in Germany is the Alps, in southern Bavaria. Geologically speaking, this mountain chain is very young as it formed in the past tens of millions of years because of the tectonic collision between Europe and Africa. The Alps are not included in this year’s Deutschland Tour, but they are the preferred setting for the feather-weight mountain goats among cyclists.

Detailed blogs on the geology of all the stages of the Deutschland Tour by David de Vleeschouwer you can find on the University of Münster website

-

David De Vleeschouwer is a geologist specializing in the study of Earth’s past climates. Fascinated by rocks and maps from a young age, he pursued geography and geology at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, earning a Ph.D. in Devonian paleoclimatology. His research focuses on understanding how small changes in the Earth’s position relative to the Sun, known as Milankovic cycles, influenced climate and ecosystem shifts before humans were playing their part. David’s global travels have taken him to Mongolia, South Africa, Illinois, and offshore Australia to study these climate cycles in the geologic record. In his free time, he enjoys running and cycling in the Bremen flatlands, the Cretaceous Münster basin, or the folded Belgian Ardennes.