Today is a long ride because it’s the longest stage of the Tour de France 2024. Stage three will take us from Piacenza to Turin, crossing 225 kilometers of never-ending croplands and fields on the largest plain of Southern Europe, the Po Plain. Most riders will surely be happy with an easy day on the flatlands before crossing the Alps. Sounds boring? Do not be fooled: there is plenty of interesting geology connected to today’s stage!

Land of passage

The third completely Italian stage of this year’s Tour starts in the city of Piacenza, in the region of Emilia-Romagna. Piacenza is famous mostly for its outstanding geographical location. It was founded already in pre-Roman times right next to the point where the important Trebbia and Po rivers join, at the transition of the Apennine mountains to the flatlands of the Po Plain.

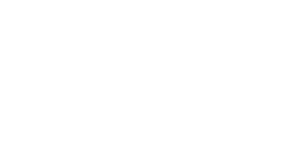

Ever since, it has been located at a major crossroads. Leonardi da Vinci even referred to the city as a ‘Land of Passage’. Like many travelers in the last thousands of years, the riders will also pass the lands of Piacenza on their way from the Adriatic coast to France. For geologists, Piacenza is famous for something else. The city gave its name to the geological stage the Piacenzian. Yes, we also like stages in geology).

The Piacenzian covers a million-year period, from about 3.6 to 2.6 million years ago. It was named after Piacenza by the Swiss geologist Karl Mayer-Eymar in 1858, because of the sedimentary rocks of that age that he found in the hills close to the city. It is not uncommon to name periods of the geological timescale to cities or geographical regions, as we could read in the previous blog about the Messinian Salinity Crisis! Interestingly, the lower boundary of the Piacenzian, the so-called Golden Spike is officially defined on … Sicily. Oops! Be careful not to tell the proud people of Piacenza!

Lucy

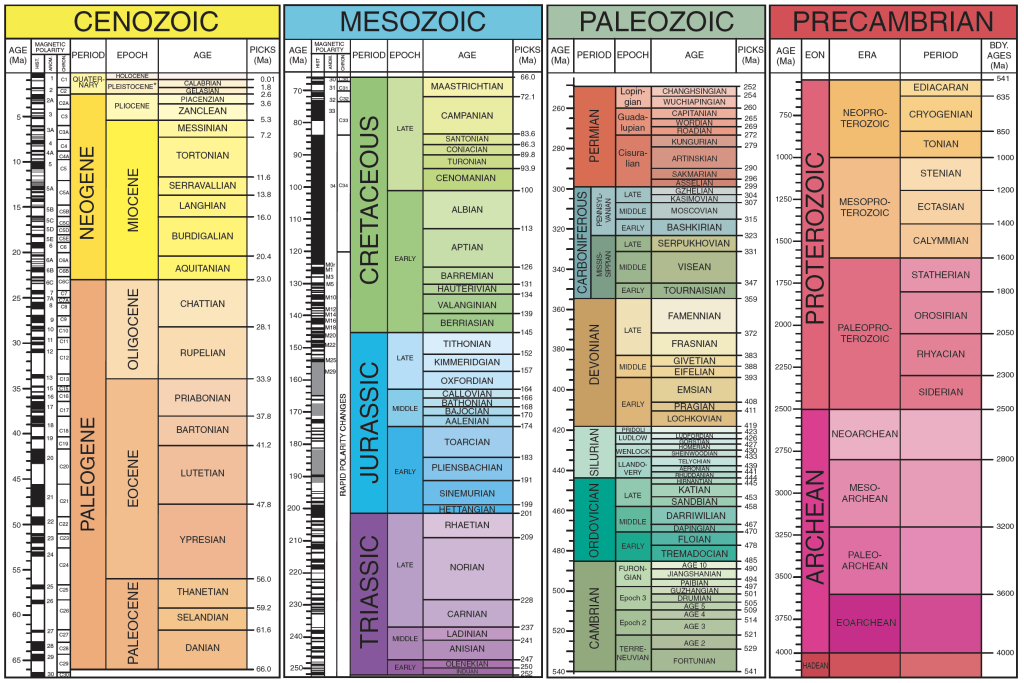

The Piacenzian may seem like a long, long time ago, just like today’s long ride to Turin. However, the history of humans may have started in the Piacenzian! Recent fossil findings suggest that the late Piacenzian may be the time when our first real ancestors roamed the planet! A fossilized jawbone found in Ethiopia in 2013 has led a group of scientists to believe that the genus Homo – to which we, the Homo Sapiens, belong – originated in the Piacenzian, around 2.8 million years ago.

Although still heavily debated, this group of scientists proposed that already during the late Piacenzian the genus Homo developed out of the more ancient genus Australopithecus. Close to where they discovered the jawbone, scientists already made an incredible discovery exactly 50 years ago. They unearthed the fossilized remains of about 40% of a female hominin. They named her Lucy. This was after the famous Beatles song ‘Lucy in the sky with diamonds’. They played it repeatedly during the excavation of the fossilized skeleton. The finding gained worldwide attention, making Lucy the most famous inhabitant of the Piacenzian! Read more about the earliest inhabitants of Europe on stage 12.

Piacenzian Park: the movie

Our ancient ancestors were surely not the only notable animals of the Piacenzian. Everyone knows the dinosaurs because of famous movies like Jurassic Park. The amazing animals of the Piacenzian are much less known, unfortunately. But if you learn a bit more about the, you really wonder why Steven Spielberg never made the movie Piacenzian Park!

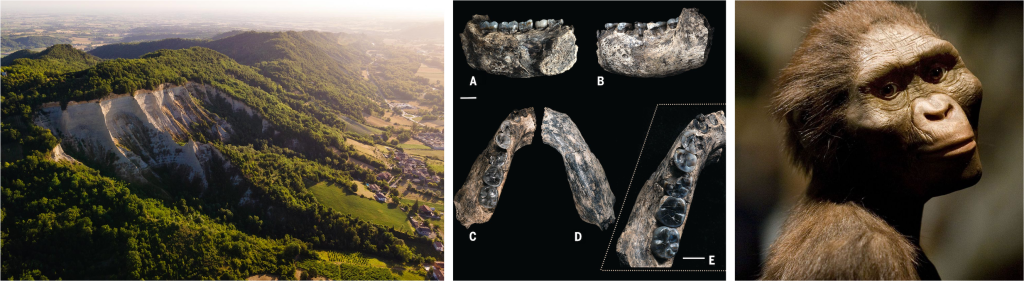

Life on Earth in the last few million years was characterized not by gigantic reptiles – like the dinosaurs – but by gigantic mammals. Scientists refer to these animals as the megafauna. Besides the already very big predecessors of present-day elephants and rhinos, there were enormous ground-sloths, super armadillos called glyptodons, as well as giant beavers and otters.

During the Piacenzian, one specific event shaped the course of evolution of many of these large animals. The final closure of the Panama isthmus – a land bridge between North and South America – allowed the exchange of different animals from one continent to the other. The Great American Biotic Interchange, around 2.7 million years ago, brought bears, large cats like jaguars, horses, and many other animals to South America. The huge sloths and terrifying flightless birds of South America, called terror birds, migrated the other way.

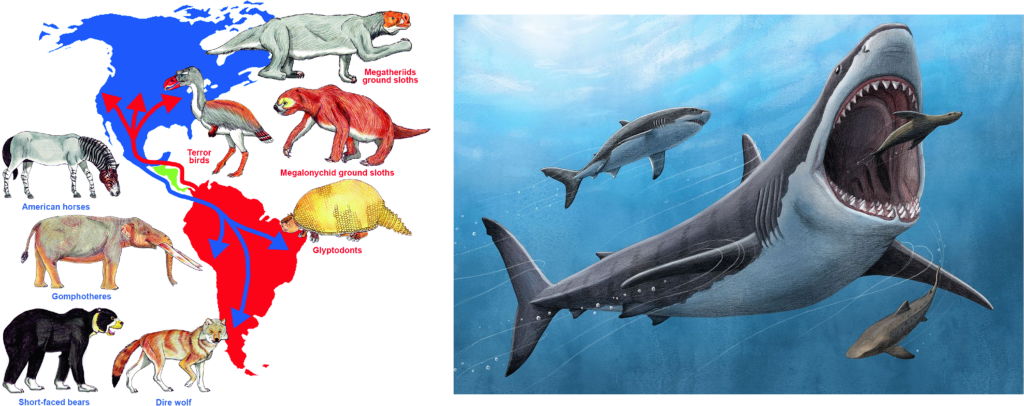

In the oceans, one predator ruled them all. This is the largest predatory shark who ever lived: the Otodus megalodon, or simply ‘Megalodon’. With an estimated length of 15 meters, this gigantic beast was the most fearsome hunter of its time. Its reign ended however at the end of the Piacenzian. The closure of the Panama gateway has been thought to lead to important changes in global climate and ocean currents, causing many marine megafauna to extinct, including the Megalodon. The Meg did get some big Hollywood movies but some of the other fascinating animals who lived in the Piacenzian could surely have their own too. Not Angry Birds The Movie, but Terror Birds The Movie. Call us, Hollywood!

Vino, per favore

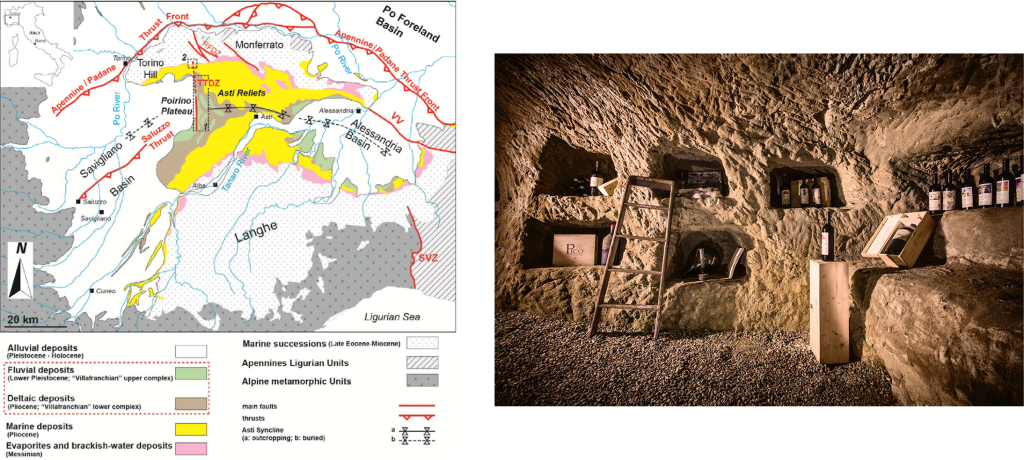

After many kilometers through the flatlands of the Po Plain the riders and viewers notice a change in scenery. From around kilometer 110, they race through the beautiful hilly landscapes of Piemonte. We know this region worldwide for its wine and not for its geology. The stage moves through the Monferrato and Langhe-Roero regions. They are listed together as UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014. Here, they produce the most famous Piemonte wines. Both the climate and (hydro)geological conditions make it a perfect region for the production of wines, most notably red and sparkling ones.

The vines grow particularly well on the subsurface consisting of mostly Miocene to Pliocene marine sediments. The most famous rocks of the region are the so-called Pietra da Cantoni. These are the local varieties of marls and calcareous sandstones from the Miocene to Pliocene. The Pietra da Cantoni were formed during a time where this region was still a shallow sea. The rocks here are full of marine fossils like shells, but also large teeth of the Megalodon have been found!

They used the Pietra da Cantoni to construct many of the buildings in the region. It is a nice showing of the local geology that is otherwise hides below the vineyards and vegetation. These rocks also serve another important purpose. They use them as a storage room for wine! For centuries, locals have dug small underground chambers into the Pietra da Cantoni, called ‘infernot’. The people here are so proud of their local rocks that they even made a museum for it, the Ecomuseo della Pietra da Cantoni!

Mysterious boulders

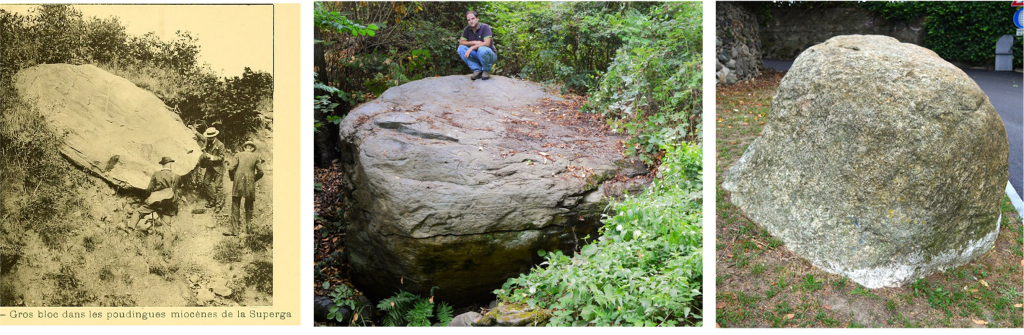

The final of today’s stage is flat, with a finish in the city of Turin close to the riverbanks of the Po. There are plenty of hills nearby though. If you watched this year’s Giro d’Italia, you might remember the steep climbs in the Torino Hills from the first stage, which also finished in Turin! In terms of its geology, the hills just east of Turin are not so spectacular. On these hills, you can see mysterious large boulders. These puzzled locals and geologists for centuries. These boulders, which vary in size from a few meters to up to ten meters in diameter, are all over the Torino Hills. They consist of metamorphic and magmatic rocks which are notably different from the surrounding marine sedimentary rocks.

Their origin fascinated early geologists for centuries, and they were already studied extensively from the late 18th century. In those early days, scientists thought the boulders arrived there by catastrophic floods. This was in line with catastrophist theories that were commonly used to explain geological observations. Nowadays, we know that these boulders are derived from magmatic and meta-ophiolitic rocks (see blog of Milan-Sanremo!) of the Alpine-Apennine mountain system. They were included in so-called conglomerates, which are the typical products of erosion of mountains. After erosion of the encasing softer and finer-grained clastic sediment around them, the boulders were left behind in the landscape.

Local lore

Before geologists studied them, some of these impressive boulders even got a place in local folklore. According to local legends, some of them were used for fertility rituals. The rock of Santa Brigida played a role in a cult in which women believed that resting their belly on the boulder favored the fertility of the mother and the good health of the unborn child. Today, local geologists are attempting to have the ‘gigantic boulders’ of Turin recognized as geoheritage sites, so they will be protected and remembered for the next decades and centuries.

Let’s see which rider will also create an everlasting memory for today’s stage. The long ride will likely end in a bunch sprint in the streets of Turin! Vai!

NB: Blogs in other languages than English are all auto-translated. Our writers are not responsible for any language and spelling mistakes.